The Radical Sex-Ed Promoted By The New York Times

On Sunday July 24th 2022, the New York Times podcast The Daily, which is the #3 rated podcast in the United States, aired an episode titled: “The Sunday Read: The Book About Sex That Every Family Should Read.” The episode highlighted and promoted the children’s book Sex Is A Funny Word by author Cory Silverberg. This book had been on our radar for about a year due to its presence on many social justice reading lists, but we were told this was a niche book that would never become mainstream. And yet here we are.

We believe this book not only promotes the idea that children can consent to sexual activity, but also promotes the removal of children’s sexual boundaries. We cannot comment on the author’s intent or the intent of the New York Times. What we can comment on is our interpretation and reactions to the book.

Some people reading this book may say that it provides excellent information about important topics such as sexual abuse, consent, anatomy, etc. Others say it is focused on inclusivity and a child-centered approach. We believe that this book superficially teaches these topics, but if read in full, one discovers nefarious concepts and messages that are deeply disturbing. Some of these include:

discouraging children from talking to parents about sex, while at the same time encouraging children to talk to other “trusted adults” about sex

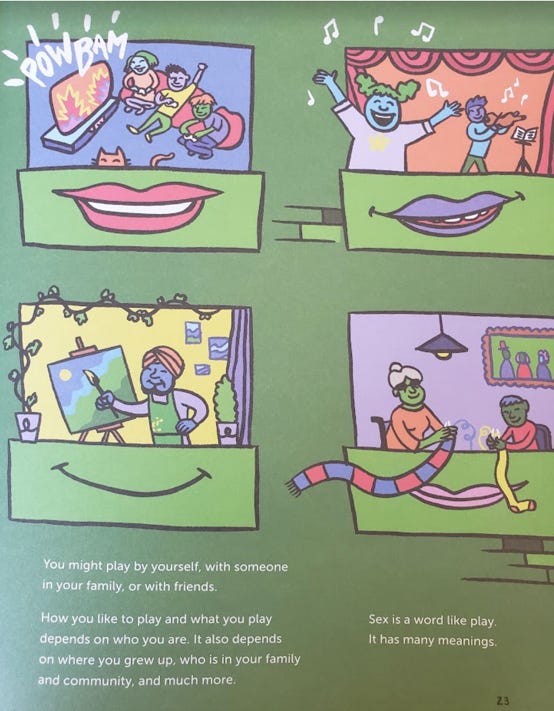

comparing the concept of “sex” to the concept of “play”

repeatedly discussing the child’s “choice” or ability to “choose” who touches them and where, thereby implying that children can consent to sexual activity

promoting the idea that a child’s subjective notion of what feels good, and what they like, are the arbiters of whether or not to engage in certain types of touching, conversations, and activities

eroding firm, clear boundaries regarding concepts of touching, sexual activity, pleasure, etc.

highlighting pleasurable sensations associated with sexual activity, without mentioning any potential negative consequences related to sexual activity

featuring disturbing images including a child masturbating in a bathtub and having an orgasm, an adult male on his knees with an erection, and more.

The NY Times appears to believe that all opposition to these types of books resides in a conservative political viewpoint, citing that the book was the “target of removal requests from schools and libraries — even before the recent surge of conservative censorship.” However, our concerns have nothing to do with political affiliation. We believe that Sex is a Funny Word promotes the erosion of sexual boundaries. The lack of inquiry into the content of this book by the reviewer, Elaine Blair, is truly astonishing. The lack of oversight that went into publishing this book review, not just on their most popular podcast, but also in the New York Times Magazine, is extraordinary. In the podcast and the magazine, Blair states that Silverberg, “...would like to see a world with no normative pressures around sex…” Taken to its logical conclusion, a world with no normative pressures around sex is a world that includes pedophilia, incest, and necrophilia.

Some would argue that this book is about sex education, but that would require providing factual and objective information. Instead this book is written in a way to make the topic of sex for prepubescent children as open-ended and playful as possible. In the New York Times profile, Silverberg states, “Some things just make you feel nothing much at all, but that’s a feeling, too… It was this idea of neutrality!” Silverberg stated that this idea of neutrality is a problem because “making a finite list of things that a reader might feel” will inevitably leave out some who do not feel that exact way. For this reason, the book appears to leave things open-ended so as to elicit an emotional response about sex from prepubescent children.

Busy parents will listen to a 27-minute podcast praising the author, skim an interview printed in New York Times Magazine, and rely on long-established institutional trust to fill in the blanks. These parents will then order the book and put it on their children’s shelf without reading it. Others will read the book, feel unsure of what to make of it, but will think that perhaps the “experts” know more than they do.

As you read the content below, we encourage you to disregard all the “experts” and instead listen to your gut responses to the images, words and messages in the book. The average parent’s visceral response to the safeguarding of their children has been eroded by the expert class’ call for “inclusivity.” When left unchecked, this is what it looks like.

The inside cover of the book states that it is for children ages 7-10:

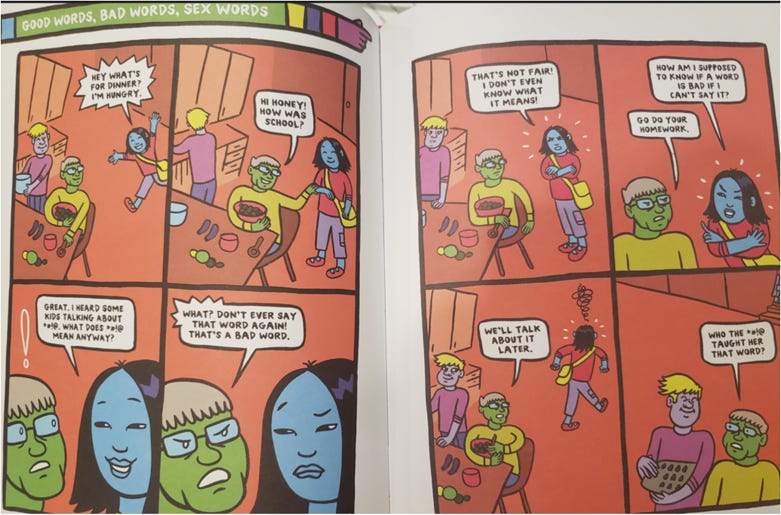

The book devalues the role of the parent when discussing sex, and appears to discourage children from talking to parents. One graphic has a child telling his teacher and classmates, “...whenever I ask my parents about sex something quite strange happens. It’s like they’re frozen and can’t move. And they get very quiet….” Another graphic has the child asking questions such as, “Dad, is kissing sex?” and “What does ‘too sexy’ mean?” with exclamation points above the parents’ heads, indicating to children that parents are not comfortable talking to them about sex. A third shows a child innocently asking the parent a question about a sexual word, only to be met with anger and punishment:

Meanwhile the book repeatedly encourages children to talk about these topics with other “trusted adults:”

The book states, “Sex is a word like play. It has many meanings.” Describing sex as playful for children has echoes of Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World. In Huxley’s dystopian novel, the state forces children to engage in “erotic play” in order to make sex purely about fun and never about love.

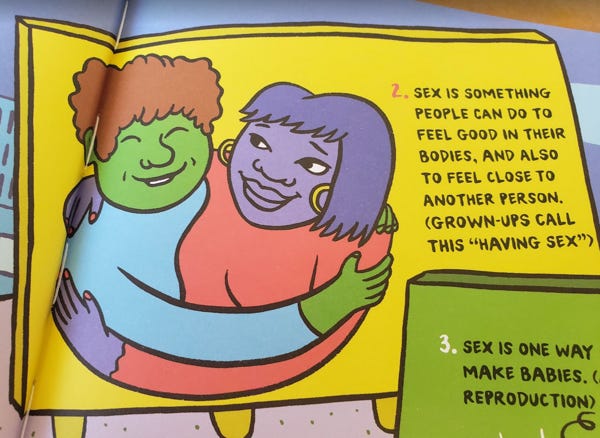

The book tells 7-10 year olds that sex is something that can feel good, or help them feel close to another person:

The book encourages children to talk about sex with people that they trust. When a child is 7 to 10 years old, someone they can trust is a person who will drive them to soccer practice, or someone who will keep a promise to buy them ice cream. Children should not be talking about sex to everyone that they trust. A child may trust a coach, but they should not be talking about sex with a coach. A child may trust a teacher, but they should not be talking about sex with a teacher. Children this young are developmentally unable to differentiate between the concept of “trust” and “sexual trust,” nor should they be expected to.

The book states, “When you trust someone, it means you feel safe and comfortable with that person. Trusting people means knowing you can count on them. It takes time to learn who you can trust….Because sex is something very personal, it’s good to talk about it with people you can trust – people you are comfortable with and feel safe around. When answering questions in this book, share your answers with people you trust.”

Many children love to make people feel happy. This book tells children that one way they can share feelings of joy is through sex:

Boundaries in this book are related to subjective feelings of what feels good and what feels bad. The book frames it in such a way that the boundary, presumably even if it’s sexual, is the child’s choice. The focus is on the child’s ability to choose who touches their private parts.

The book encourages children to question parental authority and social norms around sex. In the graphics, children say to one another, “Did you ever wonder why we have to wear clothes all the time?” and ”I mean, who made the rules? If I could, I would be naked all the time.” Another graphic shows children saying to one another, “When do you wear clothes and when is it okay to be naked? What are some things you like about being naked?”

Another graphic asks, “Do you have parts of your body you like to hide? Do you have parts you like to show?”

Now we get to the most damning two images in the book. In a section titled, “Privacy and Private Parts” is this graphic, which shows a girl with a key around her neck opening a lock box. The text states, “Keeping something private means it’s just for you. You might choose to share it with people you trust, but if it’s private, it should be your choice.”

It says that a child “might choose to share it with people you trust, but if it is private, it should be your choice.” Then it says, “There are some parts that we choose to let other people touch and other parts that are just for us.”

The book then erases the concept of private parts. By the definition below, a belly-button is the same as a child’s clitoris or penis. Just another “middle part:”

The text on the pages normalizes children wanting to see genitalia of other children, and indicates that the only reason why that would not be okay is if the other person declined to show them. In the image below, the child in the image is peering into a nudist colony. The text reads, “Learning about these body parts might make you want to see them on other people. It’s okay to be curious and want to learn, but if someone has part of their body covered, it’s probably for a reason. Respecting them means not trying to see something they don’t want to show you.”

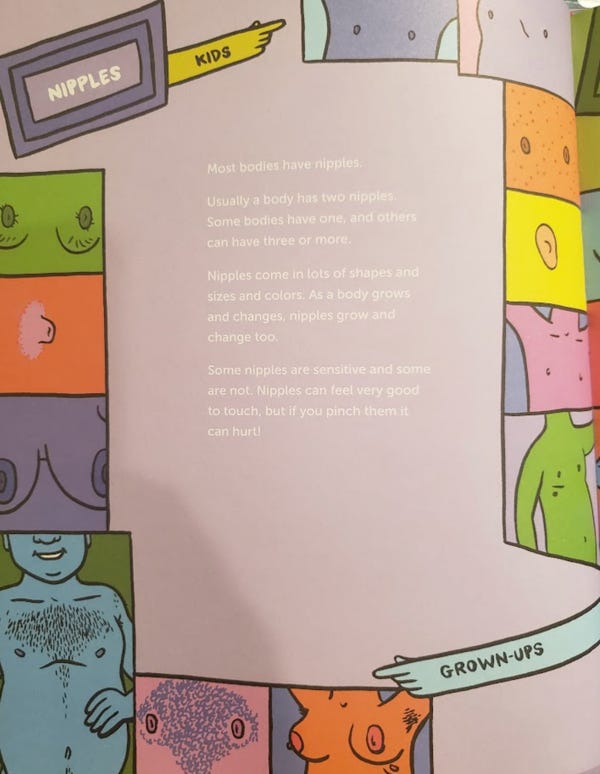

The next section of the book proceeds through the secondary sex organs using a decidedly unorthodox approach that interjects fringe or pseudo-scientific explanations with the repeated emphasis that stimulating the organs feels good. For example, consider the discussion of nipples:

The text reads “nipples can feel very good to touch.” Why is this important to a seven-year old child? Then there are comparison drawings of kids’ anuses versus adult anuses:

There are pictures comparing kids’ vaginas to adult vaginas, and the diagram on the right not only shows the clitoris, but also the “internal clitoris.” Why does a seven-year old need to know this? “The clitoris can be very sensitive, and touching it can feel warm and tingly.” Can you imagine saying this to a seven-year old?

There are drawings of three erect penises in the book. “Like the clitoris, the penis can be very sensitive, and touching it can feel warm and tingly” we are told!

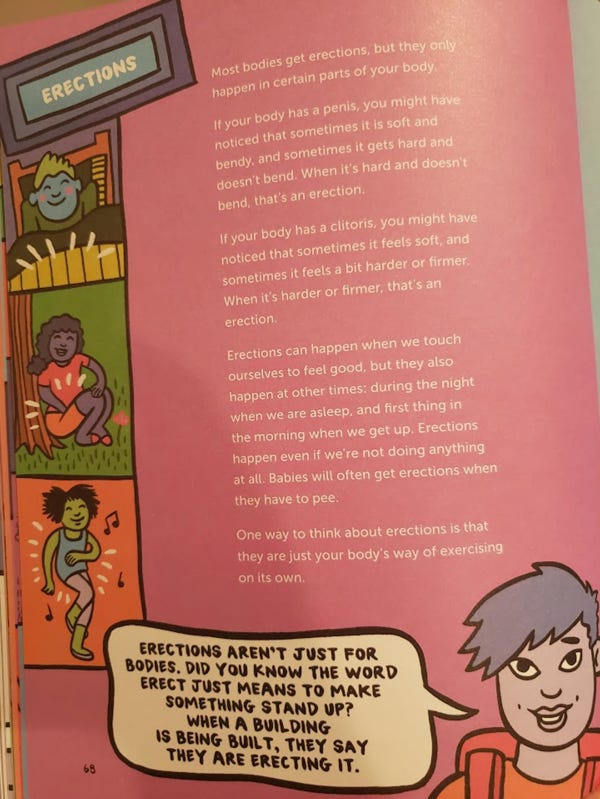

The section on erections includes a picture of a girl sitting at the bottom of a tree, pleasuring herself. The book states that girls and babies can get erections. The book then likens getting erections to exercising.

One section on touching appears to be an example of good advice in the book. It asks regarding touching, “Can you think of a time when you touched someone and it helped? What about a time you touched someone and it hurt? When is touching okay and not okay?” However, this would be true if the book offered the additional advice that some touching, such as of genitalia, is never okay. Period. Instead, this book repeatedly defers to the child’s feelings regarding whether or not the touch is okay.

The next page says, “There are times when someone might have to touch you even if you don’t want them to. Those are helping touches, but they might feel like they hurt. Whenever anyone touches you and it feels like a hurting touch, it’s okay to tell them. It’s also nice to tell people if they are giving you a helping touch and it makes you feel good.”

The page after that includes an adult asking a child, “What are some ways you like to be touched?”

This four-part graphic shows a girl in the bathtub having an orgasm. Would you want your seven-year old to read a book that depicts minor children engaging in sexual acts?

On the following page, the book equates masturbation with brushing your teeth, scratching your back, or tickling your feet. By diminishing it to just another form of touch, it equates an adult brushing against a child’s elbow with an adult touching a child’s penis. Also, why do 7-10 year olds need to know about masturbation?

In the next graphic the symbolism of the key makes a return:

The key is used to access sexual pleasure. Now recall this graphic from earlier in the book:

She has a key around her neck, and it says that she gets to “choose” who she shares with. Yet how are 7-10 year olds otherwise taught to respond when a parent or other adult in an authority position asks to see a real key they possess? Obedience to authority conditions children to immediately surrender a key in their possession.

The young readers of this book are asked if they have heard other people “use the word masturbation or talk about touching themselves to feel good.” What is missing? The directive to the child that if they hear people talking about masturbating, especially an adult, then they need to tell their parents immediately. Instead, what does the book instruct the child to do? It encourages them to question parental authority about the issue:

This is a sampling of the issues in the book; there are more, but we do not have the space to write about all of them in this article.

Most parents would not allow this book in their house. The issue is that most parents will not read it. There are not enough hours in the day, and some decisions about things like book choices are outsourced to trusted sources such as the New York Times.

We don’t know if the Times is purposely advancing these radical ideas. We do know that if you oppose sexualizing children, please consider writing to the Times expressing your discontent with their promotion of the book and the author’s ideas. If you have a subscription, consider canceling it. If you listen to The Daily podcast, leave a review or unsubscribe. If you know of anyone who has this book, send them this article. If your school has this book anywhere on the premises, contact your administration immediately.

If parents want this to stop, we need to fight back. The alternative is to be on the side that puts books like these in the hands of children. We refuse to participate in that. What about you?

The Gender Identity K-12 Team